B. Randall Tufts (1948–2002)

B. Randall Tufts (1948–2002)Obituary reprinted by permission from Eos

Randy Tufts, an explorer who made major discoveries on Earth and beyond, died on 1 April. The date surprised no one who knew him. Nationally known for his model of environmental stewardship, which stemmed from his co-discovery of Kartchner Caverns in Arizona, Tufts more recently had turned to planetary exploration and conducted path-breaking research into the geology and geophysics of Jupiter's moon Europa.

Tufts began spelunking as a high school student, and he vowed to friends that one day he would discover a cave. As with everything he did, he committed himself completely to reaching that goal. He majored in geology at the University of Arizona and combed the region for undiscovered caves through maps, fieldwork, analysis, and of course schmoozing old-time desert rats.

During his undergraduate years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Tufts faced other distractions; he became a prominent student political activist. Choosing to work within the system, he became president of the undergraduate association. By applying the same obsessive and meticulous persistence as in the cave search, he achieved reform in student rights, which was radical at the time, despite strong resistance from the university administration. After graduating in 1973, Tufts worked for a decade in social service and public policy, organizing community organizations nationwide with the federally chartered Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation. The political skills honed at school and work later proved as essential as his geological studies to the Kartchner Caverns story.

Never losing his passion for geology, Tufts continued to pursue the cave search. In 1974, with the help of college roommate Gary Tenen, he revisited a limestone hill in the Whetstone Mountains southeast of Tucson that he had first found in 1967 based on a tip from an old miner. This time the visit proved more fruitful. Following a flow of moist air aromatic with the scent of bat guano through a series of agonizingly tight crawlways, Tufts discovered what is now known as Kartchner Caverns.

Keenly aware of the vandalism that plagued other unprotected caves, Tufts realized that with discovery came an obligation and responsibility for stewardship of the resource. He and his caving partner embarked on what became a 25-year mission to find permanent protection for the cave. First they relied on a pact of strict secrecy, but soon they realized that eventual rediscovery by others was likely. They knew they needed to develop a plan to protect the pristine resource that would ensure its safety beyond their lifetimes. The fragility of the cave and its accessibility seemed to be overwhelming obstacles to protection until Tufts realized that it would make a superb tour site.

With trepidation, Tufts and Tenen approached the family that owned the land. To their great relief, they found that the Kartchners shared their respect for preservation and agreed to keep the cave a secret until it could be protected. The delicate problem of keeping potential explorers away without saying why led to interesting encounters in the desert.

On borrowed time, Tufts doggedly pursued the vision of developing a museum-quality tour cave that would be dedicated to protecting the cave and educating the public about caves and geology. After approaching the Arizona State Park Department in 1985 and receiving a less-than-reassuring response, Tufts took the plan to then-Governor Bruce Babbitt and took him through the cave. Rare for an Arizona governor, Babbitt was an environmentalist and, even rarer, had an advanced degree in geology. He elevated the cave project to the highest possible priority.

For the next 3 years, Tufts used his training in community and political organizing. He and Tenen needed to advocate, facilitate, and mediate with the Kartchner family, the Nature Conservancy, Arizona State Parks, the Arizona legislature, and local governments to keep the project on track. In 1988, the state acquired the cave. Until the park's opening in 1999 and afterward, Tufts and Tenen worked to ensure that park development would be consistent with conservation.

Tufts took a long sabbatical from his professional career in the mid-1980s, including a long around-the-world tour, in part to decide what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. During this period, he read about Jupiter's moon Europa and the possibility that there was an ocean there. Tufts recognized the potential for life to exist there, and he decided to find out if Europa was indeed habitable.

Just as he had committed himself completely to everything necessary to find a cave, he made a similar commitment to exploring Europa. And just as his search for the cave included majoring in geology as an undergraduate, Tufts enrolled in the geosciences graduate program at the University of Arizona to begin this exploration. At the same time, he began forging links with researchers at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, especially with Richard Greenberg, a member of the imaging team for the Galileo spacecraft, on its way to Jupiter, where it would obtain images of Europa.

As plans for his dissertation advanced, he had two research advisors, Victor Baker from the Department of Geosciences, and Richard Greenberg from Planetary Sciences. He did field studies of tectonics in the Mojave Desert, building expertise that he anticipated might be relevant to Europa. During Galileo's flight to Jupiter, Tufts helped interpret images of the asteroid Ida and worked the politics of astronomical nomenclature to have a crater there named Kartchner.

As Galileo images began to arrive from the Jupiter system in late 1996, Randy's attention turned at last to interpreting pictures of Europa. He discovered the 800-km-long strike-slip fault Astypalaea, and identified and characterized many other types of examples of crustal displacement. He suggested mechanisms that were later confirmed quantitatively by his colleagues, by which diurnal tidal stress could drive tectonics, including strike-slip by a walking process, and formation of the cycloidal cracks characteristic of Europa.

In the middle of the exciting 5-year period of such discovery, Tufts received his Ph.D. at age 50. His work was crucial to revealing the nature of Europa and showed that its physical setting has the potential for being hospitable to life.

Just as his search for the cave was successful, Tufts had achieved his goal for Europa as well. Next, as with Kartchner Caverns, he turned to the stewardship phase. In the last months before his illness, Tufts expressed concern that planning for upcoming spacecraft exploration of Europa's surface was not taking the possibility of biological contamination seriously enough. He understood the policy and political parallels with the cave, and his last publications (e.g., Greenberg and Tufts, 2001) addressed those concerns. The parallels between his work on the cave and planetary science are striking. The themes of commitment, exploration, discovery, and stewardship of the natural world cycled through Tufts' life. His death was widely noted and mourned, and his conservation ethic and sense of wonder were admired throughout the world.

Author

Richard Greenberg

Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA

Reference

Greenberg, R., and B. R. Tufts, Standards for prevention of biological contamination of Europa, Eos, Trans. AGU, 82, 26–28, 2001.

Originally published in Eos, Vol. 83, No. 41, 8 Oct 2002, 459. Reprinted with kind permission of Richard Greenberg and the American Geophysical Union.

Randy Tufts, Spelunker Who Kept a Secret, Is Dead at 53By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Published: April 21, 2002

Randy Tufts, who with a friend stumbled upon Kartchner Caverns, an untouched subterranean wonderland of geological creativity, and then kept it secret for 14 years, until he was confident that it would be protected, died on April 1 in Tucson. He was 53.

The cause was myelodysplastic syndrome, a disorder of the bone marrow, said his wife, Ericha Scott.

In the last chapter of his life he focused his geological expertise on one of Jupiter's moons, Europa, discovering a 600-mile-long fault there that resembled the San Andreas fault in California. He had earned his doctorate in geosciences at 50.

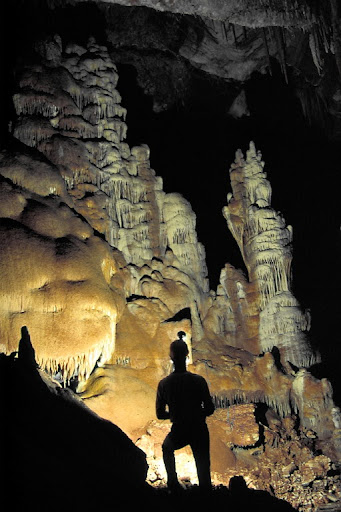

Mr. Tufts, who once said he was motivated by a longing to crawl through the next hole and see what was there, said he felt a responsibility to the human race when he first gazed at some phantasmagorical cave formations in the Arizona mountains on a cool November day in 1974.

He and Gary Tenen, whom he had introduced to cave exploration, worried that announcing the discovery of the caverns would bring tourists who might help themselves to stalactites that grow one inch in 750 years.

It took years of plotting to come up with another outcome: they persuaded Arizona to make the site into what is now Kartchner Caverns State Park. Since it opened in 1999, the first major cave made accessible to the public in the United States in decades, it has drawn 180,000 visitors a year. Visits are limited to fewer than 500 a day to protect the caverns.

The caverns have stringent technical controls: heavy steel doors keep out hot desert air, a misting system maintains a relative humidity of at least 97.5 percent and low-intensity lights inhibit algae growth.

''It is a unique status to be a living discoverer of something,'' Mr. Tufts said in an interview broadcast on National Public Radio in 1999. ''I mean, Columbus is dead. We found this cave. We're still around. We can still exercise some influence over what happens to it.''

Bruce Randall Tufts was born on Aug. 17, 1948, in Tucson. As a boy, he showed an early interest in underground spaces by digging a fallout shelter in his backyard. In 1967, when he was 18, he set the goal of finding a cave nobody else had seen.

Some miners told him about a sinkhole in the Whetstone Mountains near the Mexican border. He found the pit and discovered a narrow crack leading into a jumble of rocks.

''We concluded it was a blind hole, going nowhere,'' he told The Arizona Daily Star. But he marked the location in his records.

At the University of Arizona, he was student body president. After graduating with a degree in geology, he became a community organizer and then worked as a field officer for the Neighborhood Reinvestment Corporation, pressing banks reluctant to lend in minority neighborhoods.

In 1974, he sought out the sinkhole that he seen seven years earlier. He spotted a horizontal hole 60 yards from the sinkhole and theorized that the two openings indicated cave passages between them. He told Mr. Tenen of his theory, and the two soon tested it.

''We went down to the bottom of the sinkhole, and everything seemed the same as before except for one thing: There was a breeze coming out of the crack we'd found before,'' he told The Star. ''It was warm, moist air -- and it smelled like bats!''

The breeze and bat scent suggested that the narrow passage led to somewhere large enough for bat colonies. Mr. Tenen, who was smaller than Mr. Tufts, crawled through a 10-inch-wide crack first. Mr. Tufts then took off his shirt, exhaled and wiggled through.

''It was like being born all over again,'' Mr. Tufts said.

They then crawled over a floor covered with bat guano and hackberry seeds, seeing no sign that a human had ever been there. After 25 feet, the tunnel stopped. With a three-pound sledgehammer, they broke through a bedrock barrier.

They saw a multitude of stalactites, pointing to their mirror images, stalagmites. Some rock formations hung like draperies; extraordinarily thin stalactites resembled soda straws. The colors were dazzling: blood red, deep purple, delicate orange and yellow.

Secrecy became almost an obsession for the two men. They sneaked into the area and carefully covered any caving gear left in their car. They hid from passing drivers and hunters.

But the cave was near a road, and caving clubs were already exploring nearby. ''If we discovered it, somebody else could,'' Mr. Tenen said. ''It was inevitable.''

They hit upon the seemingly paradoxical notion of protecting the cave by opening it to the public, but with scrupulous safeguards. They visited commercial caves and attended caving conferences.

They learned that the land was owned by James Kartchner, a rancher, science teacher and superintendent of schools. He was amazed and pleased to learn about the cavern, having long noticed a hollow sound as he rode his horse over the site.

The campaign to make the cave a state park included taking Gov. Bruce Babbitt -- who signed their standard secrecy agreement threatening violators with divine punishment -- to see the cave. In 1988, the State Legislature passed a bill approving the cave's purchase. The language was deliberately opaque, and only six legislators knew they were buying a cave.

Mr. Tufts then turned his attention to Europa, using images from the Galileo spacecraft to study how tides cause shifts of the moon's crust.

Richard Greenberg, a University of Arizona professor of planetary science and a member of the Galileo imaging team, said Mr. Tufts's work ''was central to showing that Europa is a place whose physical setting may well be hospitable to life.''

Mr. Tufts is survived by his mother, Carol Tufts; his sister, Judy Rodin; and his wife, Ms. Scott, whom he married in October 2000, three days before he entered the hospital for a bone marrow transplant.

Ms. Scott said he loved life and would interrupt a desert hike to reverently bury a dead bird. Just as he protected the cave, she said, he wanted to establish safeguards to protect whatever life might exist on Europa from damage by spacecraft.